The Wright Building

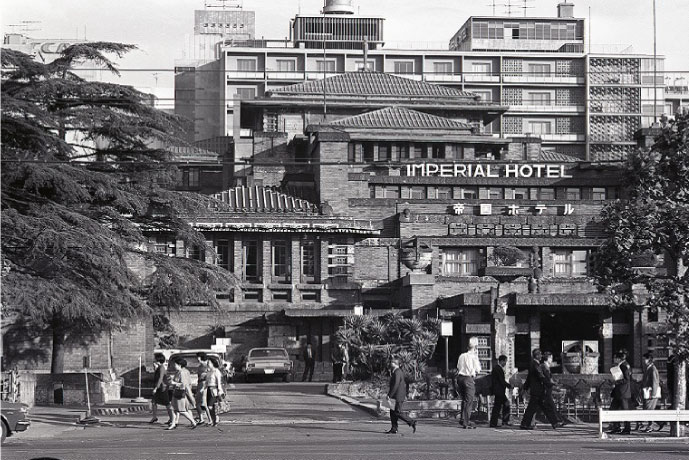

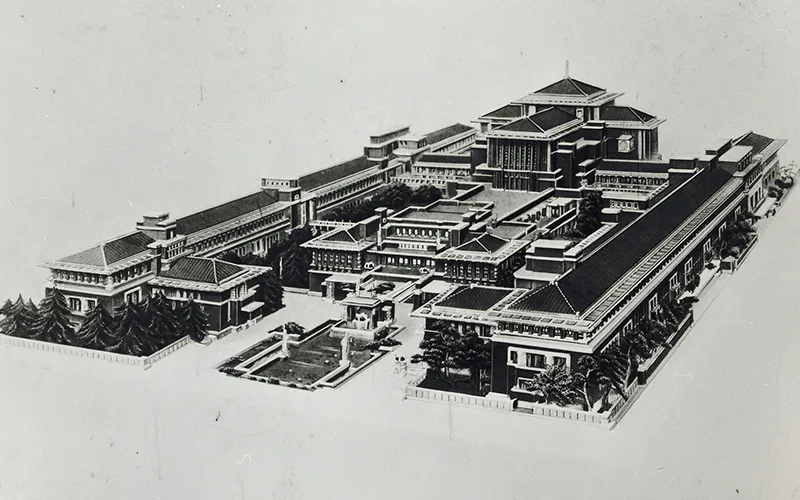

The second-generation main building of the Imperial Hotel was designed by the American architect, Frank Lloyd Wright. Known as the Wright Building and Wright’s Imperial, this creation by Wright functioned as a bridge between the East and West of the era. In addition to its beautiful architecture, its services and products emit a radiance that earned it the nickname “the Jewel of the Orient.”

Wright Building

The Imperial Hotel opened in 1890, serving as Japan's guesthouse to welcome guests from abroad. It played a role in the development of Japan's modernization and westernization, as well as in improving the presentation of Japan overseas. Located next door was the Rokumeikan, a stage for glamorous socializing and diplomacy.

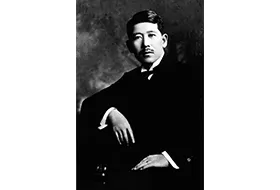

In 1909, Aisaku Hayashi became the first Japanese manager of the Imperial Hotel, due to the efforts of Eiichi Shibusawa, the first chairman of the Imperial. Prior to that time, the 36-year-old Hayashi had been an antique dealer at Yamanaka Shokai in New York. Having lived in the United States since he was 19 years old, Hayashi was highly familiar with Western tastes and ideas, and was also very knowledgeable about luxury hotels.

He significantly enhanced the Imperial’s operations through the introduction of new facilities, equipment, and guest services. Innovations included the establishment of a mutual aid association for the welfare of employees and their families, the introduction of double-entry bookkeeping to ensure accurate and reliable accounting, and the establishment of a post office and a self-operated laundry in the hotel (a first in Japan) to serve guests staying at the hotel.

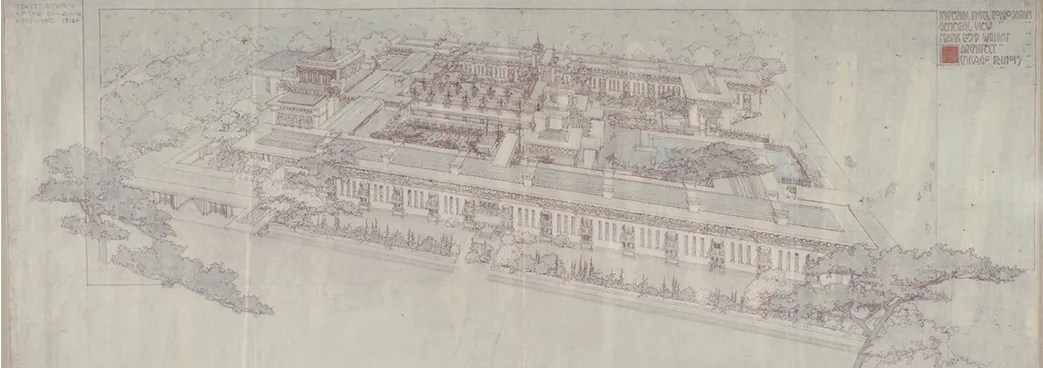

Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation Archives (The Museum of Modern Art | Avery Architectural & Fine Arts Library, Columbia University, New York) All rights reserved.

However, the most substantial challenge was the renovation of the main building. The aging wooden structure, which had stood since 1890, was not only in need of refurbishment but was also unable to handle the growing influx of visitors. Thus, a modernized main building, capable of meeting contemporary demands, was deemed necessary.

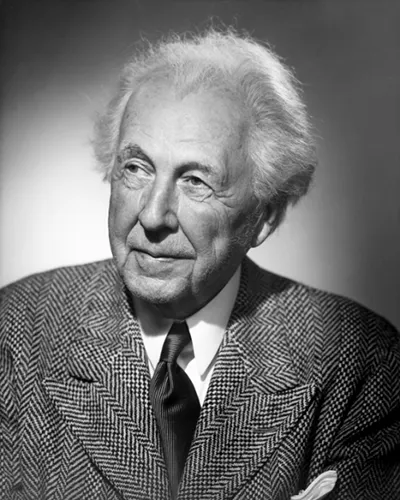

From a pool of potential architects for the job, Frank Lloyd Wright was selected to design the new edifice. Hayashi knew of Wright due to Wright’s collection of ukiyo-e woodblock prints, and through mutual acquaintances, he learned of Wright’s architectural achievements. In 1913 Wright traveled to Japan to meet Hayashi to discuss plans for the new hotel. In March 1916, Hayashi journeyed to the United States and entered into a memorandum of agreement that awarded the Imperial Hotel commission to Frank Lloyd Wright, who triumphantly departed for Japan later that year.

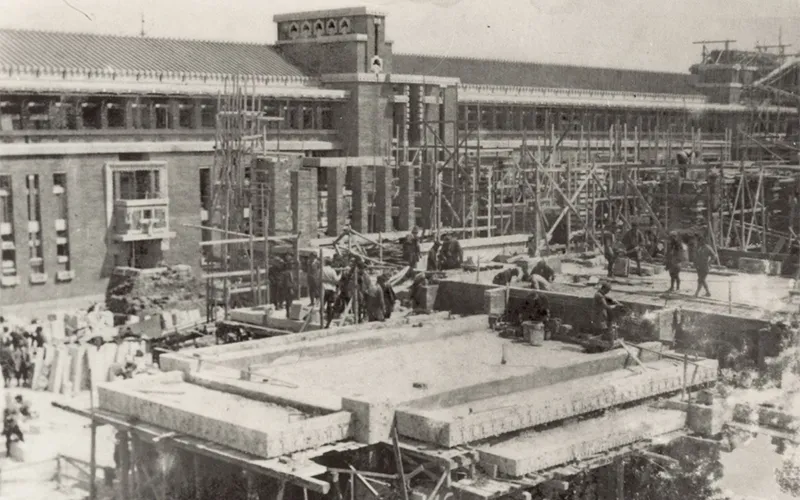

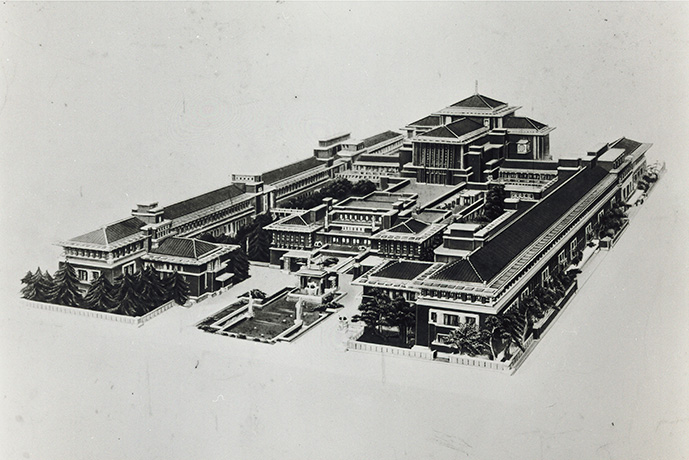

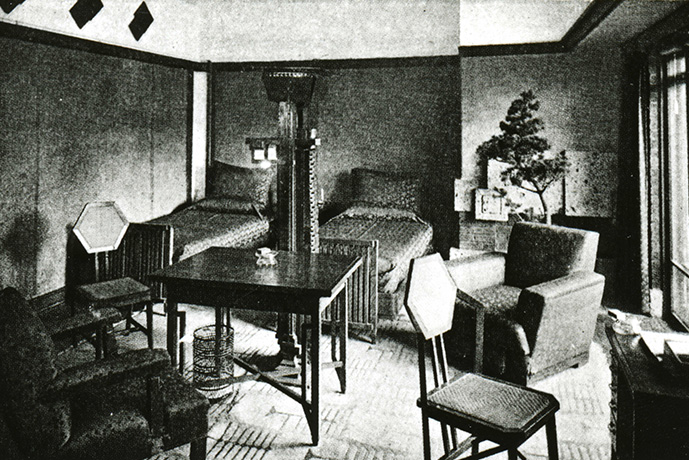

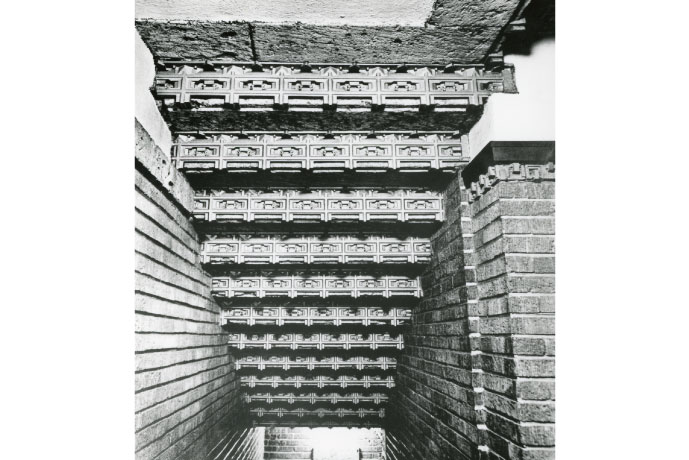

Wright lived on the grounds of the Imperial Hotel site and spearheaded the hotel's construction. Oya stone mined in Tochigi Prefecture and yellow baked bricks and tiles produced in Aichi Prefecture were used in large quantities as building materials. Additionally, Wright designed the interior decor, furniture, tableware, and additional elements, each bearing the geometric patterns that were a hallmark of his architectural style. Furthermore, despite the trend of rising urban verticality in Japan during this period, the guest rooms in the Wright Building were limited to three stories above ground. This design feature, characteristic of Wright's architectural style, blended harmoniously with the verdant surroundings of Hibiya Park and the nearby Imperial Palace.

On the very day it was inaugurated - September 1st, 1923 - the Great Kanto Earthquake struck the region, yet the Wright Building managed to withstand major damage, and for 44 years continued to serve not only as a place to stay, but also as a venue for gatherings and cultural exchanges.

Architect Frank Lloyd Wright (1867-1959)

Born in Wisconsin, USA, Wright is one of the three great Masters of Modern Architecture. His passion and love for Japanese art was so great that his first trip outside the United States was to Japan. Beyond the Imperial Hotel, Wright left other architectural works in Japan, many of which profound influenced Japanese architects. His impact continues to resonate not only in large-scale public edifices, but also in contemporary residential design. Wright is credited with designing over 1,100 structures, nearly half of which were ultimately constructed. Currently, eight of Wright's buildings are registered as UNESCO World Heritage sites.

Culture Originating from the Imperial Hotel

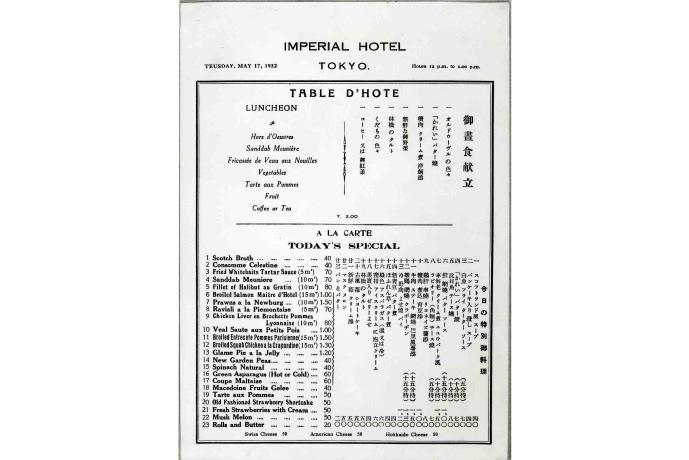

Some examples of hotel culture that originated in the Imperial Hotel during the Wright Building era and are still carried on today.

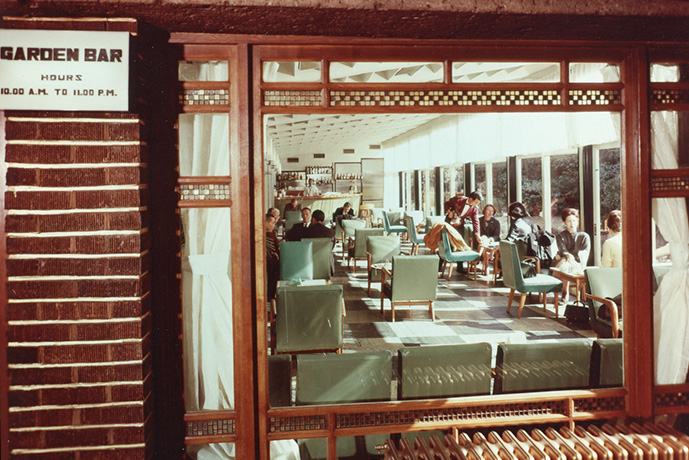

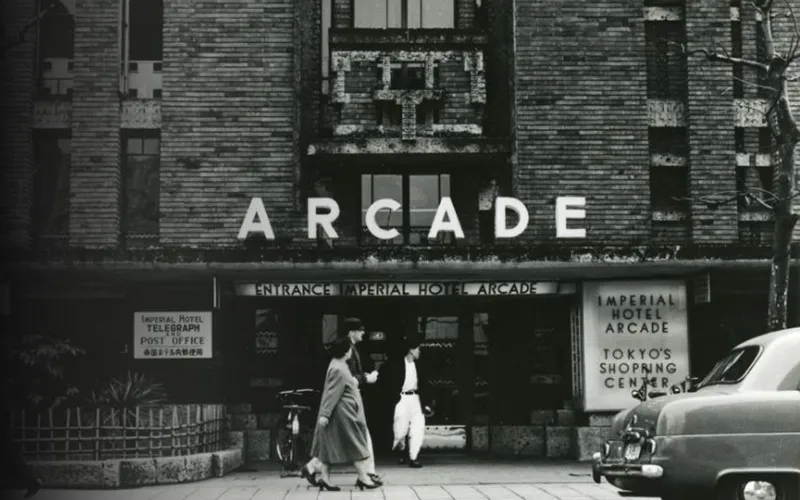

Hotel arcade supports the enjoyment and convenience of staying at the hotel. When the Wright Building opened, there were 19 stores; today there are approximately 50. The criteria for opening stores at that time was that they had to represent Japan in terms of traditional arts, and with respect to cultural and technical standards.

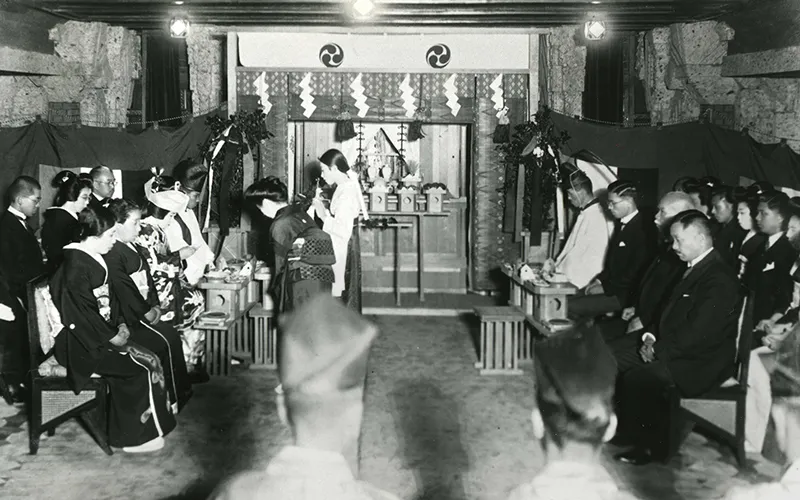

Since many shrines and temples in Tokyo were destroyed by the earthquake that happened on the day Wright Building opened, a shinto-shrine which guests could use as a wedding hall was built in the hotel. This established an environment in which ceremonies and receptions could be held in one facility. Even today, this is the most representative style of weddings held in Japan.

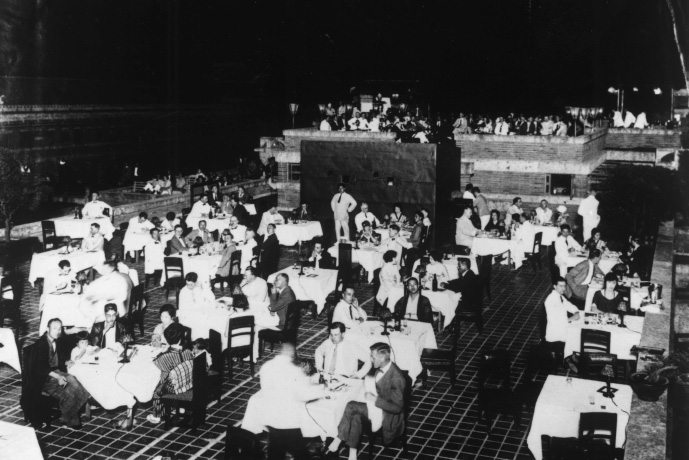

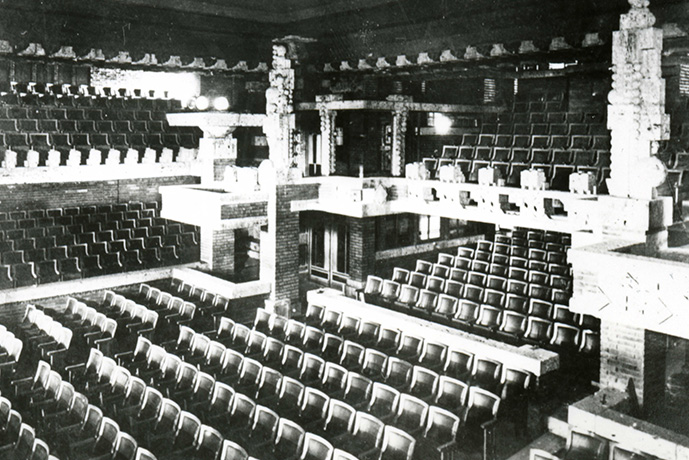

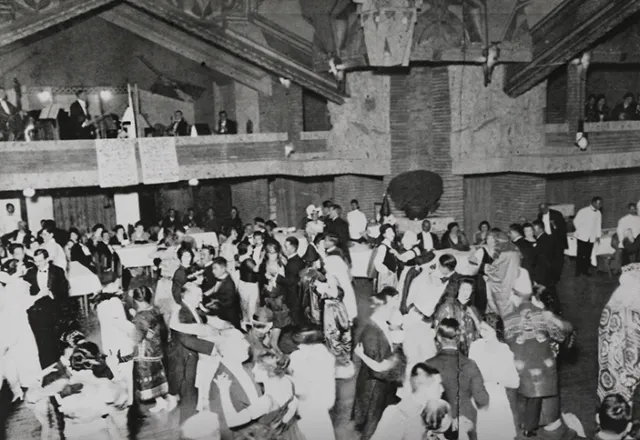

The hotel's grand banquet hall, the Peacock Room, which could accommodate approximately 1,000 people, was used for parties and balls. Varitey of receptions styles, from wedding receptions to dinner buffet parties were held. The 850-seat theater, which also had projection equipment, hosted performances, plays, concerts, and movie screenings.

Additionally, the hotel entered into an exclusive agreement with the Hatano Band, Japan's first salon orchestra, which was a forerunner of jazz bands. This partnership provided a platform for professional musicians to showcase their talents, and significantly contributed to the introduction of Western music at the hotel. It was a pivotal initiative, akin to the idea that understanding a country's cuisine is a stride towards international understanding. This led to the inauguration of Food Festivals representing various countries.

A Place for Socializing

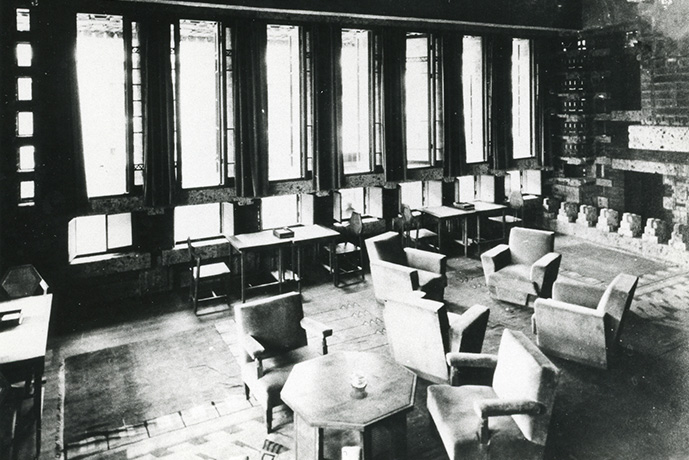

The Wright Building was a place where people gathered. Not only the use of space, which was characteristic of Wright's architecture, but also the banquet hall, promenade, salon, court garden, rooftop terrace, restaurant, and other public areas where people interacted with each other occupied half the area of the hotel. Most of the guests were foreigners, but there were also many Japanese visitors. They mingled, attended parties held at the hotel, and used the restaurants. Guests came to the hotel on a variety of occasions. The hotel played an important role in connecting people and countries, and was a center for cultural exchanges.

Column

Two Stories About the Wright Building

Vicariously experience the Wright Building, known as the "Jewel of the Orient," from two perspectives: recollections of a hotelier who worked at the Wright Building at the time, and a curator who researches the preserved Wright Building. From there, we then imagine the future.

Yukiko Koike, Hotelier: Marilyn Monroe's Visit to Japan

—— One night in February 1954, an eleven-year-old Yukiko Koike saw the Imperial Hotel for the very first time.

There on the TV set in the living room of her home was the sight of Hibiya Park, packed full with onlookers. A massive structure that mixed both Eastern and Western styles stood at the center of the chaos, and there on its second-floor balcony bordered by complex Oya stone reliefs was a foreign actor, waving her hand. Every last one of the countless camera lenses pointed in her direction. The newscaster explained who she was: a movie star by the name of Marilyn Monroe, in Japan on her honeymoon with Joe DiMaggio.

At a press conference held in a building in the Imperial Hotel known as the Wright Building after its world-famous architect, the actor answered a journalist's question as follows.

"What do you wear to bed?"

"Chanel No. 5."

A hotel visited by world-famous superstars. When Koike saw this, she thought, "I want to work in this hotel someday." Strangely enough, her dream was to work in it, not stay in it.

"If I work here, I thought, I'm sure I'll be able to meet gorgeous people like her every day," she laughs as she recalls her grade-school self.

—— Koike has since gone on to work at the Imperial Hotel for sixty-two years. She is now the only active employee with experience working at the Wright Building.

Yuko Nakano, Museum Meiji-Mura:

The Beauty Conveyed to the Modern Day by the Wright Building

—— One day in 2023, Yuko Nakano, curator at the Museum Meiji-Mura, tried calling yet again.

She was searching for furniture used inside the Wright Building when it was still operational because of the upcoming special exhibit celebrating the Wright Building's centennial. She'd used materials left to her by her predecessor to finally discover someone who once exhibited such furniture at a Frank Lloyd Wright exhibit. She had even managed to find their contact information, but the owner of the furniture had yet to pick up the phone even once.

The Museum Meiji-Mura is an outdoor museum that opened its gates in 1965 where visitors can see relocated works of Japanese modern architecture. Sixty-seven buildings, including residences, a local government office, a church, and more sit on its roughly one million square meters of land in the area of Inuyama, Aichi's Lake Iruka. A steam locomotive imported from Britain even runs on premises. It's here that the entrance lobby of the Wright Building has been preserved.

"Meiji-Mura opened out of a desire to preserve the architecture destroyed under the shadow of Japan's rapid economic growth for future generations as cultural assets. Even among those structures, the Wright Building is special."

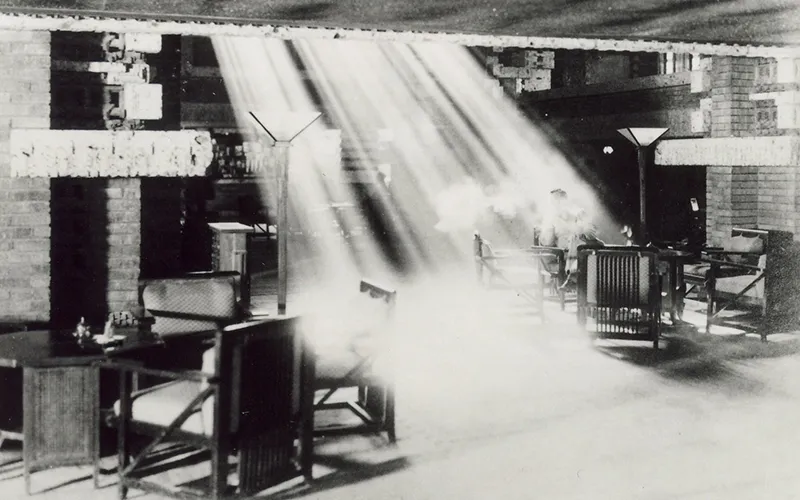

Nakano, who is responsible for surveying and research, is constantly surprised by the new discoveries she makes about the Wright Building. It is designed so that it is in harmony with the outside environment, with openings throughout it allowing light and air to flow through.

There's a slight glimmer in the interior of the dim room, with its pillars made of Japanese Oya stone and terracotta baked in Tokoname, Aichi, as well as the gold-colored ornaments placed all around. The Wright Building is also home to many unique details among Frank Lloyd Wright's work.

"While it's hard to imagine that there's a Japanese architecture influence at first sight, we can find areas with a connection to uniquely Japanese spaces, such as shoji paper screens and tea houses."

The ceiling to the entrance is lower than a standard hotel's. Its staircases and halls are also designed to be intentionally narrow, in strong contrast to the lobby's open atrium. Nakano likens this to the small entrance found in Japanese teahouses. Still, she says, there are some elements she has yet to understand.

Multiple patterns can be found in the complex Oya stone carvings that are not present in the original design documents at the time of construction. Records state that Wright created these extemporaneously after discussions with Japanese stonemasons.

"It's precisely because the building is from the recent past that we're faced with the challenge of never being able to exhaustively study it. There are still a lot of mysteries when it comes to the interior spaces of the Wright Building in particular."

Almost all of the Wright Building's chairs, tables, tableware, carpets, and so on were sold or disposed of before its preservation at Meiji-Mura. Nakano is now consulting various resources from the time in the hopes of bringing life back to the building's interior.

—— Yet again, the furniture's owner didn't pick up. Nakano decided to write a letter instead.

Yukiko Koike:

Remembering a Place to Shine

—— One morning in 1962, Koike heard two well-dressed college students speaking on a tram as she got off at the station closest to the hotel.

"One day, I'm going to stay at the Imperial Hotel too."

That same day, Koike was assigned to the first-floor guest rooms in the south wing of the Wright Building. A year had passed since she had applied to the Imperial Hotel through the girls' high school she attended, took the company entrance exam, and joined as a room clerk in March 1961.

She was assigned to the #2 Annex (formerly the East Building) for her first year, where she was taught the basics of service. She first learned how to clean guest rooms, then just as she began feeling at home delivering room service with a wheeled cart, her chance arrived to work in the very same building where Marilyn Monroe stayed. While thrilled, Koike also felt a faint sense of anxiety, having only just stepped into the world of hotels.

"For whatever reason, my seniors at work seemed hesitant about working in the Wright Building. It made me wonder what kind of place it could be."

She would come to learn that reason soon enough.

Service in the Wright Building was nothing like the annex. There were no separate roles for laundry, cleaning, and food. The work was almost akin to a butler's or a maid's, where one had to perform every service relating to an assigned guest's room and take care of them in every way possible. The employee corridors were barely wide enough for two people to brush past one another, and she practically needed to shoulder food trays as she climbed up and down the narrow stairs. She wore dress for ease of movement during the day and a kimono at night to give a sense of Japanese senses, both of which became drenched with sweat. It was hard for her to believe that two facilities could be so different within the same Imperial Hotel. She keenly felt just how much of a contemporary hotel the annex she'd come from had been.

And yet, she was certain she found herself in a place to shine.

The world opened up when she exited those employee corridors. Natural light filtered through stained glass made shadows on the stone reliefs waver, and the brass tips inlaid on the walls glimmered.

Even the customers who came and went in the lobby looked different. While the annex was primarily used by Japanese guests for business, the Wright Building's guests were almost entirely visitors from abroad, and long-term guests at that. She would visit the guest rooms to deliver room service, reaching out to doorknobs placed higher than average for easier use by Westerners. Amidst her hectic workdays, there was one place Koike found herself standing still for a change. In front of a corner window in a south wing hallway.

"The Wright Building was famous for being in harmony with nature and having a view of the garden, but I was too busy to ever look outside. The one time I could take a deep breath was when I stood in front of that window. Streetcars went back and forth on Hibiya Street, and past it you could see the Imperial Palace. It's the one view I can remember from the Wright Building."

She could hear the sound of a violin being played somewhere. A musician visiting Japan must have been staying in the hotel. There was something exotic about the inside of this building they called the "Jewel of the Orient." It's what Koike loved about it.

"It was a kind of homelike atmosphere. Some guests would even return with gifts for us, like one person ordering food for two, then telling me 'Thank you for everything. This one's for you.' Everyone there was so kind and humorous."

For whatever reason, Koike was given meals from guests more often than her coworkers. She says her seniors would tease her, saying "I bet you must always have a hungry look on your face."

Late one night, she walked through the darkened hotel with her seniors. After climbing the stairs, she found herself facing a wide-open space. It was the banquet hall, also known as the Peacock Room. It wasn't a place she normally visited as someone not assigned to banquets. She strained her eyes to get a look at it in the dark.

"I wish I could've seen the banquet hall with the lights on just once," she laughs.

—— Five years later, the Wright Building would close.

Yuko Nakano:

A Desire to Leave Something Behind

It was decided in 1966 that the Wright Building would be closed and rebuilt as a new atrium. The shock of this news reached beyond even Japan's borders. At the center stood the conservation efforts made by a support group of Japanese architects known as the Society to Preserve the Imperial Hotel. Should the "Jewel of the Orient," a standout work by a world-renowned master that had survived both a great earthquake and a World War as it continued to host many state guests, really be destroyed? The group assertively approached both politicians and the media.

It seems, though, that the facts of the matter looked grave. Though the building had made it through disaster and conflict, it remained damaged, and it now suffered from differential settlement. There was no choice but to rebuild if the hotel wanted to continue to host guests, but the fate of the Wright Building was now turning into an international topic of discussion.

Then, in a November 1967 press conference following a Japan-US summit between President Lyndon B. Johnson and Prime Minister Eisaku Sato, the prime minister suggested moving a portion of the Wright Building to Meiji-Mura.

The statement was printed as front-page news, and wheels began to turn. Still, the prospects for this preservation plan were as unclear as they could be. Even if it was limited to the entrance lobby, how would the reinforced concrete structure be carried the 350-or-so kilometers to Meiji-Mura? Its restoration would be an unprecedented feat of construction.

After returning to Japan, Prime Minister Sato approached Yoshiro Taniguchi, then the director of Meiji-Mura, about the plan. There was little time left. It was only at the last moment that Meiji-Mura made a decision.

"I think it was a very painful decision for both the Imperial Hotel and for the Museum Meiji-Mura, as well as an extremely difficult challenge," Nakano says.

The method they had thought up was one of "preservation in form." Reusable decorations collected from the Wright Building would be used alongside new materials in a concrete structure with more strength than before in Meiji-Mura to reproduce the front lobby in a nearly complete state.

Construction was completed in 1985, all of eighteen years since the building's closure.

"Wright once said that architecture creates culture. We believe that architecture speaks to history," Nakano says.

Now, Meiji-Mura is undertaking a new challenge.

In 1998, Meiji-Mura greatly changed the way its buildings are displayed. The museum's policy is now one of "restoring spaces," recreating the atmosphere of the time within the structures that had previously been used as exhibition rooms.

"The buildings themselves have an incredible amount of value on their own, of course. But their interiors are what bring scenes experienced by the people inside of them back to life. Wright himself considered furniture to be a part of a building."

Nakano opens a newspaper scrapbook from the time.

"After the Wright Building's closure, about 4,000 pieces were sold to the public, from furniture to even chandeliers. Reports say that customers came flooding in from around the country, and that they sold out before they knew it. There are still 4,000 pieces somewhere out there."

Nakano and the Museum Meiji-Mura will continue to pursue the Wright Building.

—— The letter Nakano sent would later arrive as intended. She says she was contacted by someone claiming to be related to the furniture's owner.

Yukiko Koike: Continuity

In November 1967, Koike received a notice after having been transferred to the #2 Annex (formerly the East Building). "Employees may take mementos from the Wright Building home with them." Koike was focused on the customers standing in front of her, but she couldn't help but feel a sense of sadness about the closure of the Wright Building, the place that built her foundation as a hotelier.

"My seniors took home things like chairs. I chose one of the Oya stone reliefs."

Koike would go on to take various posts, including manager, and was even responsible for the reception of many state guests. Soon, though, she'll be retiring from the Imperial Hotel.

"We are all excited about the new main building. I think I'd be working there if I were twenty years younger. That's just how important the Imperial Hotel has been in making me who I am as a person. It all started with the understanding of service I learned at the Wright Building. Now I'm the only one who knows about it. I'll be sure to pass that knowledge on to the colleagues staying behind."

A hundred years after the Wright Building's opening, the beauty and philosophy depicted by Frank Lloyd Wright lives on in different locations. This "place to shine" that Wright left behind in Japan and the time that so many people spent inside of it lives on in today's Imperial Hotel as the ideal a hotel should strive for. As the Imperial Hotel Tokyo's main building is scheduled to be rebuilt from 2031-36, it too will carry on that brilliant glow of the "Jewel of the Orient."

Elements of the Wright Building

handed down to the present day

Old Imperial Bar

The mural and Oya stone relief originally located above the fireplace in the Treasure Room in the Wright Building, have been preserved and are now exhibited behind the counter of the Old Imperial Bar, the current main bar of the Imperial Hotel. The wall there even showcases some of the terra cotta that was used during the initial construction.

Frank Lloyd Wright® Suite

Opened in 2005, the Frank Lloyd Wright® Suite is a unique space, the sole suite globally endorsed by the Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation. It integrates elements from the erstwhile Wright Building, including Wright's authentic carpets, furniture, and lighting fixtures. Moreover, it brings together design inspirations from Wright's masterpieces across the United States, all reimagined within the confines of a hotel room.

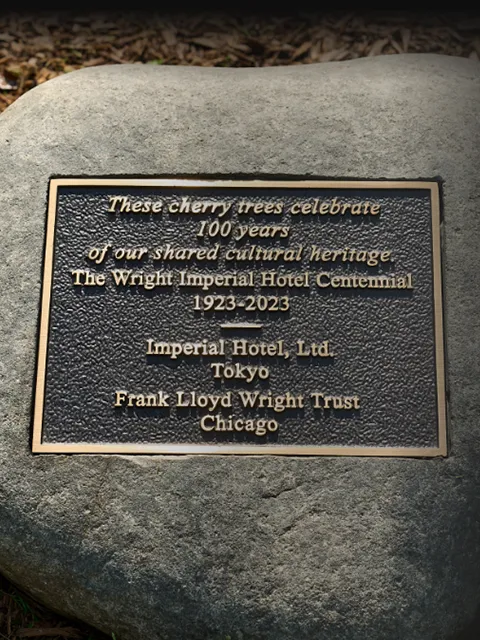

Centennial celebration

Imperial Hotel and the Frank Lloyd Wright Trust celebrated the 100th anniversary with a private dedication of cherry trees planted in the courtyard of Frank Lloyd Wright’s Frederick C. Robie House, Chicago, a UNESCO World Heritage site, and a masterpiece of the Prairie Style and a forerunner of modernism in architecture. Guests gathered to commemorate Wright’s legacy in Japan and the United States.

Hoping the cherry trees flourish for many years to come, in honor of Wright’s achievements.

Photos: Michael Moenning Photography

These cherry trees celebrate 100 years of our shared

cultural heritage.

The Wright Imperial Hotel Centennial

1923-2023

Imperial Hotel, Ltd., Tokyo

Frank Lloyd Wright Trust, Chicago

Outline of Facilities

Imperial Hotel Second Main Building, commonly referred to as the Wright Building

1-1, Uchisaiwai-cho 1-chome, Chiyoda-ku, Tokyo Japan

three floors above ground (five floors in parts) and one basement level

site area: 156,442 square feet, building area: 76,865 square feet

270 guest rooms, restaurants, banquet halls, theater, arcade, library, post office (at opening)

| 1890 |

The Imperial Hotel opens.

|

|---|---|

| 1900 |

Aisaku Hayashi begins working at Yamanaka Shokai's New York branch. (1900-1909) |

| 1905 |

Frank Lloyd Wright's first visit to Japan. |

| 1909 |

Aisaku Hayashi becomes the first Japanese manager of the Imperial Hotel.

|

| 1916 |

Aisaku Hayashi signs a memorandum of agreement with Frank Lloyd Wright in Chicago, USA. Decision to construct the Wright Building taken at extraordinary general meeting of shareholders. Frank Lloyd Wright visit to Japan concerning the construction of the Wright Building. |

| 1917 |

Frank Lloyd Wright nears completion of design of Wright Building. |

| 1918 |

Frank Lloyd Wright visit to Japan concerning the construction of the Wright Building. After that he came to Japan a total of four times to focus on the hotel construction. |

| 1919 |

Construction of Wright Building begins. |

| 1920 |

Partial completion of new annex building designed by Frank Lloyd Wright. |

| 1922 |

Partial opening of Wright Building. Banquet hall and Theater of the Wright Building are completed. |

| 1923 |

September 1st. The Wright Building opens, and the Great Kanto Earthquake strikes during preparations for the opening ceremony. Rooms provided as offices for affected companies, newspapers, news agencies, and embassies. Theater leased to the Imperial Theatre and other theaters damaged by the earthquake.

|

| 1924 |

Exclusive contract signed with Hatano Band.The hotel helps to popularize classical music and jazz in Japan. |

| 1965 |

Holding of first food event, Swiss Food Festival. |

| 1967 |

All guest rooms in the Wright Building are closed. The Wright Building lobby and vestibule to be moved to Meiji-mura in Aichi Prefecture, Japan.

|

| 1970 |

The new Main Building (now the Imperial Hotel Tokyo`s Main Building) opens. |

The New Main Building Plan The Jewel of the Orient

Plans are in place to rebuild the Imperial Hotel Tokyo’s main building. This is aimed at maintaining its status as a beacon of "Made in Japan" hotels for the next 100 to 200 years. The research conducted by architect Tsuyoshi Tane, ATTA – Atelier Tsuyoshi Tane Architects, has led him to take into Account not only the Imperial Hotel but also the broader Hotel industry. Following its manifesto ‘Archaeology of the Future,’ the design will merge the structure of a “palace” that welcomes distinguished guests with the modernistic "tower" symbolizing human progress. Tane’s new, unique guesthouse, intended to shine brilliantly in the heart of the capital city, embodies a concept that seeks to carry forward the legacy of the "Jewel of the Orient" - a term used to describe the Wright Building - into the future.

"Imperial Hotel Tokyo New Main Building Image Perspective by Tsuyoshi Tane"

This is in the preliminary stage and subject to change as developed.

Movies

Gallery

MEMBERSHIP

Members of the Imperial Club International enjoy a vast array of privileges.

The membership is free of charge and you can apply online.

Digital Account for the Imperial Hotel

Digital Account for the Imperial Hotel

ID offers you exclusive complimentary or discount coupons, as well as seasonal announcements and the latest information delivered straight to your inbox.

Imperial Club International

Imperial Club International

We invite you to apply for Imperial Club International membership at no charge through our website.